If you grew up singing in the Portland metro area today, it might be hard to imagine a time when community youth choirs weren’t everywhere. But when I was in high school (1984-1988), they simply didn’t exist. School choir was the only pathway, and whether you found your way into a life-changing program depended entirely on who your teacher was. I happened to have one of the best.

At Rex Putnam High School, John Baker built the kind of choral program that didn’t just teach us to sing, it taught us to understand music. He was one of the first directors I knew who made sight-reading a daily part of rehearsal. We used to sight-read from old hymnals that he had received from one of the local churches and he taught us the very basics of music theory and he even created a study hall where he taught more advanced music theory to anyone who wanted to learn. For those of us without an instrumental music background, these lessons were life-changing. Looking back, I know without question that it was my ability to read music, far more than the quality of my voice, that opened the door to my professional choral career. I owe so much of that foundation to John.

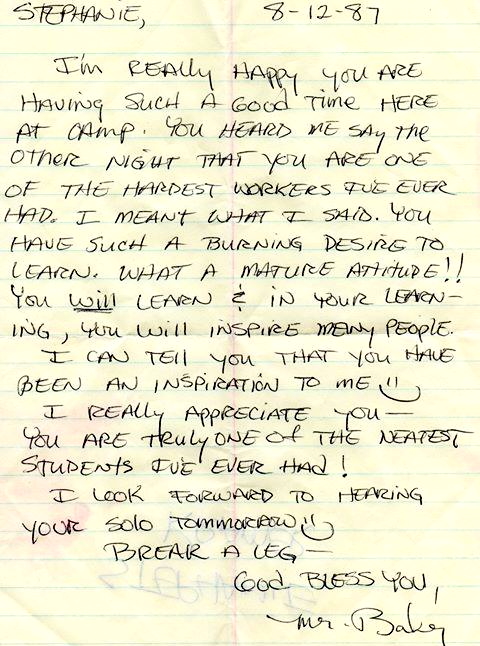

This note was written to me by John while I was at the Frank Demiero Jazz Camp in Edmonds, Washington in August 1987, the summer between my Junior and Senior years. It captures so much of who he was as a teacher, taking the time to encourage and support his students not only through his words and actions, but also in writing. I still have this note 38 years later. I know that countless young singers have been lifted up by his kindness and belief in them.

When I asked John recently what led him into music education, he shared that it was not something he had originally planned. As a senior at Newport High School, he placed first in state in the Bass voice category. Someone important in his life encouraged him to try studying music in college, telling him, “You never know where it may take you.”

“When I applied for music at Oregon College of Education, I was given a fifteen-page music exam. Though I excelled in choir and trombone in band, I had not learned much theory. I only managed to get my name and date correct on the exam. A college professor encouraged me to major in sports instead. I told him my goal was to see whether music might play an important role in my future. He said, ‘Don’t waste your money, you will never pass theory.’ I asked him why. He replied, ‘Because I am the music theory teacher, and there is no way you will pass.’ I asked, ‘Can you stop me?’ ‘No,’ he said. After graduation and getting hired at Rex Putnam HS, I realized music theory was very important to help singers learn to read music. My goal was simple: teach them everything I know. At that point in my life I knew little, so I emptied my brain in hopes they would learn.”

His approach eventually became the topic of his master’s thesis, “Teaching Sight Reading to Choir in Daily 5 Minute Segments.” Not only did the method work for Rex Putnam, but the thesis went on to sell over 1,000 copies in the Pacific Northwest, and John was invited to present his sight-reading workshops at ACDA and MENC conventions. What we experienced in choir every day was a carefully thought-out philosophy of education that shaped hundreds of students.

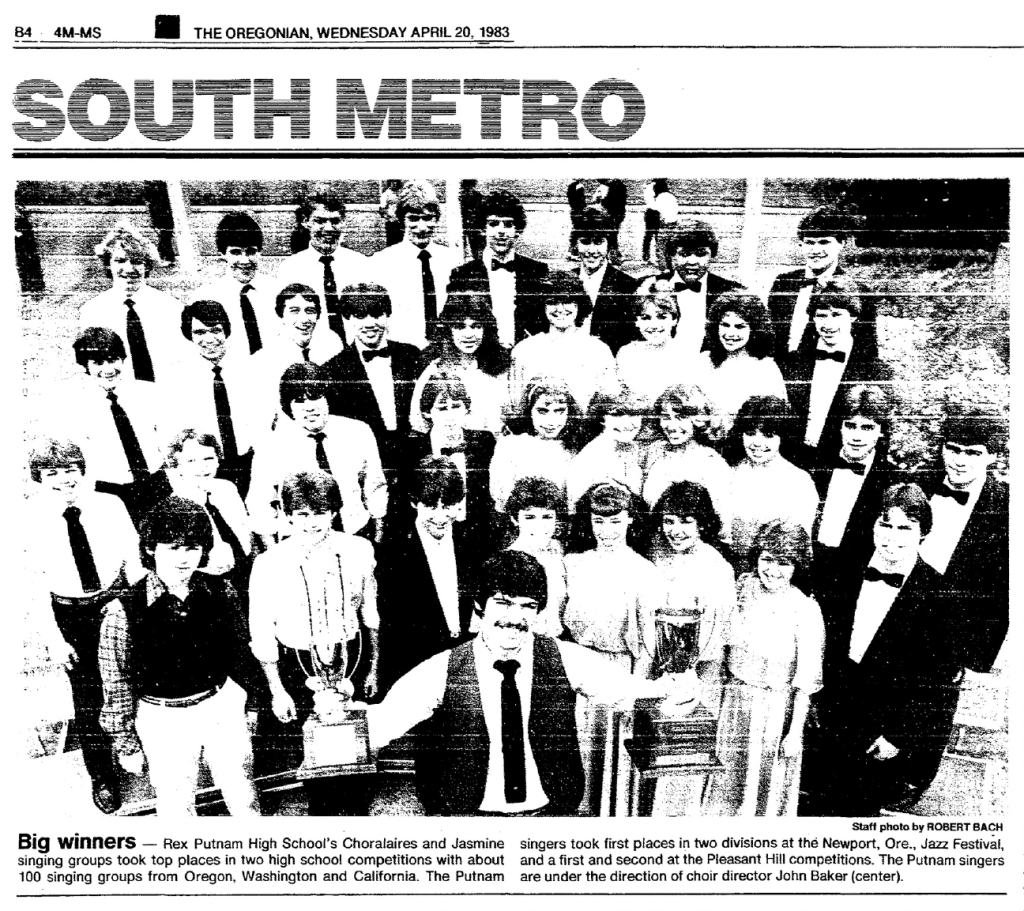

At Rex Putnam, John built a nationally respected high school program, one that combined musical excellence with an emphasis on literacy, discipline, and passion. Under his direction, Rex Putnam regularly performed at the highest competitive level, and his students developed the kind of confidence and expressiveness that inspired many of them to keep music in their lives long after graduation. Many of John’s students went on to become professionals in music careers, either singing, producing, or teaching music.

When I asked him recently how it feels to see so many former students still singing or working in music today, his answer was beautifully simple: “Warms my heart! For others to experience the joy and fulfillment of a music related career is wonderful. For many, music as an avocation involves less pressure and still provides the joy and adrenaline rush that makes live performances valuable. In my case, the joy was so evident that I believe I never worked a day in my life”.

Beyond the walls of our choir room, John’s influence stretched across Milwaukie and far beyond. When budget cuts in the early 1990s eliminated most elementary school choir programs, he refused to accept a future where children had no access to meaningful music education. Together with his wife Sandy (who also taught choir in the North Clackamas schools and happened to be my very first vocal coach in 1985), he launched what became the North Clackamas Children’s Choir and a summer choir camp, programs specifically designed to give children the opportunity to learn to read music, develop healthy singing habits, and discover the joy of choral singing long before they reached high school. What began as a modest group of about two dozen kids quickly grew into a thriving musical community, eventually serving more than a hundred young singers every year and helping sustain a choral pipeline that otherwise would have disappeared.

Even decades into his career, John was still advocating fiercely for arts education. In a 2010 Oregonian feature connected to an OPB “Oregon Art Beat” special, he spoke candidly about how arts programs can appear strong on the surface while quietly eroding underneath due to budget pressures and shrinking participation. Today, he continues to hold both hope and concern for the future of music education. He is encouraged by teachers who “exude the knowledge, energy and enthusiasm necessary to encourage our future music makers,” and he believes there are still powerful and inspiring programs around the country. At the same time, he worries about the lingering impact of COVID, especially as even strong programs work to rebuild participation. He remains firm in his belief that committed music students excel across many areas of learning, and that music should never be the first thing cut.

John retired from teaching at Rex Putnam in 2011, but he never stopped teaching, never stopped building community, and never stopped creating spaces where people could sing together with purpose and heart. Today, he directs the choir at Milwaukie Lutheran Church and leads the Tilikum Choir Community, where his lifelong commitment to accessible, meaningful choral singing continues. In true John Baker fashion, he has woven his past, present, and future students together, regularly inviting former Rex Putnam Choralaires to reunite and sing with the Tilikum Choir for their holiday concerts. It feels like the most fitting continuation of his life’s work: still nurturing voices, still building community, still reminding people of every age that music belongs to them.

JOHN’S MENTORS

Like any great teacher, John is quick to acknowledge the mentors who shaped him, recognizing how their influence helped form the teacher, musician, and leader he became.

Richard Nace taught him the art of private voice instruction within a choral setting, and helped him understand how crucial it is to communicate meaning expressively, not only vocally, but facially as well. He also introduced John to the powerful emotional practice he called “Upsession,” opportunities for choir members to share feelings and build trust, vulnerability, and deeper connection with one another.

Rod Eichenberger, internationally respected conductor and beloved choral figure, served for many years as clinician for Rex Putnam’s choir retreats between 1998 and 2021. From Rod, John learned that “less is more” when it comes to conducting, and that singers learn the most not when the conductor is talking, but when they are singing.

One of John’s most profound mentors came from outside the music world altogether: legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden. In 1984, John came across Wooden’s book “They Call Me Coach,” and it became, in his words, a guiding text for how to treat students, how to build discipline, and how to lead with humility and fairness. Wooden’s insistence that every player—star or not—be both humble and committed deeply influenced John’s approach. He began to think of music literacy and sight reading as the “conditioning” of choral singing, just as Wooden conditioned his athletes to outlast everyone on the court. “It worked,” John said simply. He wrote to John Wooden twice over the years, and both times Wooden replied in handwritten letters, which John still treasures today.

Looking back now, as someone who has spent decades singing professionally and building much of my adult life around choral music, I see just how deeply John Baker shaped that path. He did not simply teach us notes and rhythms. He taught discipline, curiosity, responsibility, and joy. He gave us the tools to walk into rehearsal rooms with confidence and to know that we belonged there. In every concert I’ve sung, I’ve carried his teaching with me. I will always be grateful that I was one of his students.

Selected Sources

Steele, Jeanette. “Summer Songs.” The Oregonian, 30 June 1994.

Trujillo, Laura. “Dedicated to Do-Re-Mi.” The Oregonian, 22 June 1995.

Nix, Nelle. “At Choir Camp, Everyone Gets in on the Act.” The Oregonian, 27 June 2002.

Lawton, Wendy Y. “Singing Their Hearts Out.” The Oregonian, 3 May 2002.

Turnquist, Kristi. “The Arts for More Than Arts’ Sake: How the Arts Helps Teach in Schools.” The Oregonian, 27 May 2010.

Personal interview with John Baker, December 2025.

Leave a comment