What It Really Means to Serve on an Arts Nonprofit Board

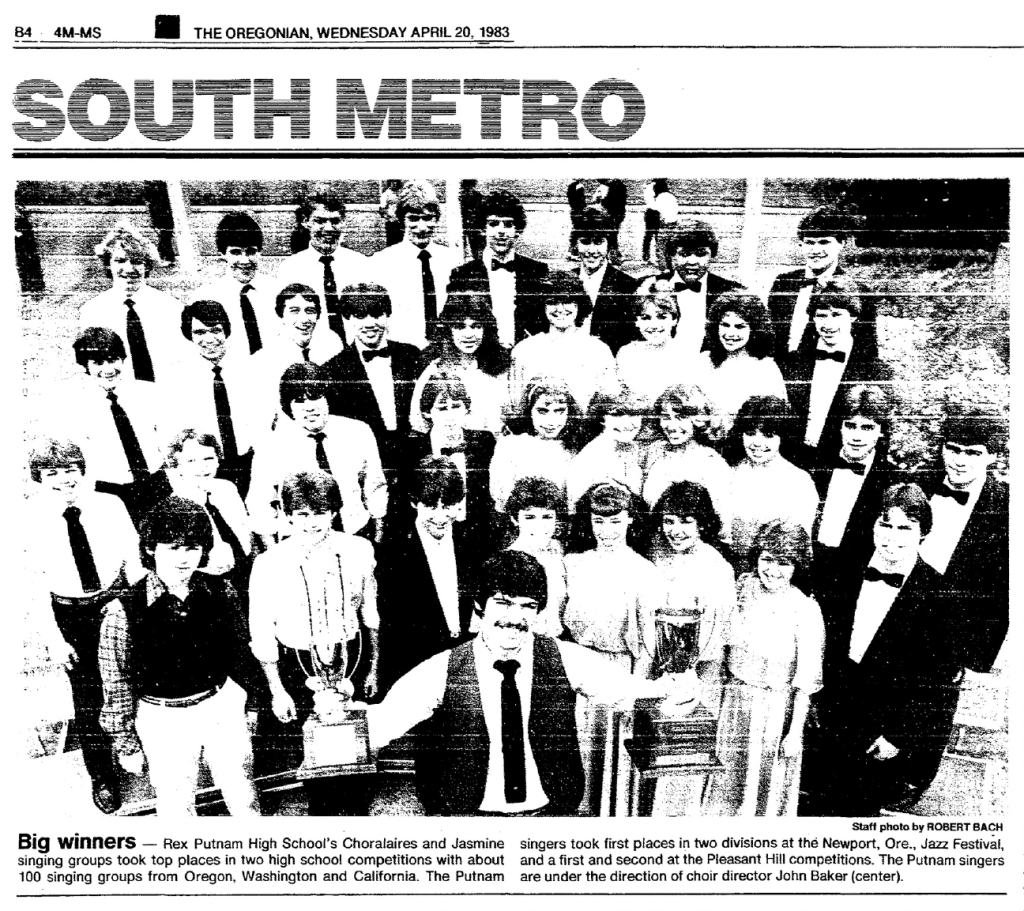

Over the years, I’ve experienced arts organizations from a lot of different angles, as a singer, as an administrator, and as a board member. I’ve served on the boards of Cappella Romana, as a singer representative, and Resonance Ensemble, as Managing Director. This month, I’m beginning board service with In Mulieribus, an ensemble I care deeply about.

Stepping into this new role has made me reflect more intentionally on what board service actually means in the arts. Not the abstract version, and not the version that lives on websites, but the lived, human version of it.

If you spend enough time in the arts world, eventually someone will ask you to serve on a board. It usually happens because you’ve been showing up in some way, attending concerts, volunteering, and advocating for an organization. It means someone believes you are thoughtful, dependable, connected in the community, or passionate enough about the organization to help guide it forward. But there is often a gap between the idea of serving on an arts nonprofit board and the lived reality of it. Arts boards quietly shape whether organizations grow, stall, fracture, or flourish

So what does serving on an arts nonprofit board really look like?

It’s Not Just Paperwork (and It’s Definitely Not Just Prestige)

At its most basic level, a board exists to govern, not to run the day-to-day operations. Boards are responsible for mission, long-term health, leadership oversight, and financial stewardship.

But good governance goes far beyond bylaws and budgets.

Chorus America speaks about board culture as something that’s shaped, not inherited, and that “boards don’t move forward by accident; they do so with intention.” I love that framing, because it reminds us that board culture doesn’t just happen. It’s shaped by how people listen, how disagreement is handled, whether curiosity is encouraged, and what ultimately guides the decisions that get made

It’s worth saying plainly: serving on a board is not a ceremonial role. It isn’t a social club or simply attending performances with your name in a program. It is service. It asks for attention, responsibility, and a willingness to engage even when the work is largely invisible.

What Arts Board Members Actually Do

Every organization structures this a little differently, but most arts boards spend their time in a few core areas: stewarding mission, guiding strategy, overseeing finances, supporting fundraising, and hiring and supporting executive leadership.

Arts Consulting Group, which works with arts organizations all over the country, often emphasizes how central board leadership is in the arts. They note that “board leadership is a core element in the success of all nonprofit organizations and perhaps more so in the unique arts and culture sector.” That line really resonates with me. Arts organizations live at the intersection of meaning and money, beauty and infrastructure. Strong boards understand that complexity and help organizations stay steady inside it.

In other words, boards don’t exist to choose programs or tweak marketing copy. They exist to help create the conditions that allow the art to exist at all.

What Makes Arts Boards… Arts Boards

Arts organizations live in a funny in-between place. They are built on passion, beauty, meaning, and human connection. But, they are also built on spreadsheets, grant cycles, budgeting, and long-range planning. Arts boards are constantly navigating that space.

What makes arts boards different from many others is that the “product” is not a service or a solution. It’s an experience. It’s something felt. It’s meaning, sound, story, and presence. That makes the work both deeply human and quietly complex.

Arts Consulting Group and others often talk about the particular balance arts boards hold: financial sustainability alongside artistic risk, tradition alongside innovation, internal identity alongside outward relevance. Arts boards help organizations stay steady while also making room for creativity to unfold.

What Good Board Service Feels Like

Good board members show up. They read their materials. They ask real questions. They listen more than they talk. They support staff without crossing into staff roles. They understand that clarity doesn’t usually arrive fully formed. It often comes through conversation, questioning, and sometimes disagreement.

They also understand that the people in the room shape the future of an organization. Who they are and what they bring to the table both matter.

Healthy boards build cultures where people can think out loud, change their minds, and care deeply without burning out.

Small Arts Organizations: A Different Kind of Work

Board service may look very different depending on the size of an organization. My husband is on the board of the Oregon Symphony, and while my original thought was that their strategic plan would look much different from ours, he reminded me that the ultimate goals are basically the same: attracting audiences, supporting musicians, nurturing artistic excellence, and maintaining a secure revenue stream.

What changes is how those goals are carried out. In a large institution, board service often lives at the level of long-range planning, major campaigns, and organizational oversight. In a small organization, those same goals are often felt much more immediately, in decisions about staffing, resources, and how to stretch limited capacity without breaking it.

In large institutions, boards often operate at some distance from day-to-day operations. In small arts nonprofits, boards are much closer to it. Sometimes right in the middle of it.

Arts Midwest’s writing on governance for arts organizations notes that smaller organizations often operate with what’s known as a “working board,” where board members fulfill not only governance responsibilities but also operational tasks when budgets and staff are limited, something that brings the board closer to the day-to-day life of the work.

In small organizations, you feel the impact of decisions quickly. You see the wins. You also see the vulnerabilities. Supporting a small arts nonprofit often means helping build structures that can hold the work over time, not just in this current season of energy and devotion.

Why People Say Yes

The people I know who serve on arts boards don’t do it for titles. They do it because they love an art form. They love a community. They believe that something beautiful deserves their care and commitment.

There is something quietly powerful about helping sustain work that is not easily measured. About helping artists do what they do. About contributing to spaces where people gather, listen, reflect, and connect.

Board service can also stretch you. It teaches patience. It teaches understanding of how things connect and how decisions ripple outward. It teaches how to keep listening when the path forward isn’t obvious

The Parts People Don’t Always Talk About

Board service takes time. It often includes financial expectations. It sometimes includes difficult conversations. It can involve uncertainty, slow progress, and decisions where there is no perfect answer.

Arts organizations live close to vulnerability. Funding shifts. Audiences change. Leaders move on. There are seasons of uncertainty. Boards are part of holding all of that.

Good board members don’t disappear when things get uncomfortable. They stay curious. They stay engaged. They stay present.

Thinking About Serving?

If you’re considering board service, it’s worth asking yourself some gentle but honest questions:

Do I really believe in this mission?

Can I give this time and attention, not just affection?

Am I willing to learn how governance works?

Can I support leadership while also speaking up when something doesn’t sit right?

Do I want to help build something that will outlast me?

Often, board service begins because a current board member or staff member reaches out and asks if you would be interested. But it doesn’t always have to start that way. If there is an arts organization you truly care about, and you feel you have something meaningful to offer, it is completely appropriate to approach them and ask whether they are recruiting new board members or committee volunteers. Arts organizations are grateful when people raise their hands thoughtfully and express interest grounded in genuine care.

A Final Thought

Arts organizations don’t survive on applause alone. They thrive because artists create, audiences show up, communities care, and boards quietly help hold everything together. Serving on an arts nonprofit board is not about prestige or proximity to the “cool” parts of the arts world. It is about care, responsibility, advocacy, and heart.

If you already serve on a board, thank you. If you are considering it, I hope this gives a clearer sense of what the role really means. When boards are strong, thoughtful, and committed, the entire arts ecosystem benefits.

Selected Sources

Chorus America. “Aligning Board Culture with the Mission and Moment.” Chorus America.

Arts Consulting Group. “Arts and Culture Leadership: Four Action Steps to Create a Stronger Board.” Arts Consulting Group.

Arts Midwest. “Healthy Approaches to Board Governance.” Arts Midwest.

Leave a comment